The Dating Game

Published by Masque & Spectacle on September 1, 2025 https://masqueandspectaclejournal.wordpress.com/2025/09/01/the-dating-game-leslie-lisbona/

I was nearing thirty, and I knew I wanted to find a husband and have children one day soon. I worked as a credit analyst in a bank in midtown and lived at home with my mother in Queens. This wasn’t unusual for kids of immigrant parents; it was out of the question that I would move out before getting married. So I was considering my options.

There was the man in Mexico, who had wanted to marry me ever since our first kiss, when I was 19 and he was 20. We’d been on again, off again all that time.

And there was the man who worked in my department at the bank and smelled like expensive French cologne. He was tall, close to six feet, with dark wavy hair. His eyes were an emerald green, and it looked like he wore eyeliner even though he didn’t. He was a year younger than I. Our desks were a few feet apart, separated by a grey cubicle partition.

Like my parents, he was from Lebanon. He spoke English with an accent, and his French was as good as mine. His sense of humor and his joyfulness felt familiar. But my parents were Jews from Beirut; he was Muslim, from Tripoli, a city known for its sweets. Though he lived in New York, his plan was to return to his country. “You and I together would be impossible,” he joked.

“Totally,” I said.

“My mother would kill herself, right after she finished making the kibbe,” he said. And we laughed and laughed.

He smoked and drank coffee all day long. Sometimes the two of us would slip out to Au Bon Pain on 40th Street. Other times I would join him in the bank’s crowded smoking room, my eyes stinging, just to spend my break with him.

I suspected he liked me more than he was letting on. So once, when he asked me what I had done that weekend, I said, “Oh, I met the cutest guy at a party. He definitely works out.”

“Really?” he said. “What’s his name?” He had stopped smiling.

“Val,” I said.

He blew a puff of smoke up between us. “That’s a fake name,” he said.

I couldn’t help grinning. “He is also Muslim, by the way, like you.”

Val, in his black T-shirt, had the most beautiful body I had ever seen. The boys I usually liked were bookish and never set foot in a gym, but Val clearly lifted weights, probably daily. His silky black hair fell over arched eyebrows. His olive skin made him glow, like he’d recently returned from the south of France. We had danced together at the party, but I told him I was not available. Soon after, he became my best friend’s roommate, and I began to see him all the time.

One morning on my way to work, I was running down the steps to the subway platform in Forest Hills to catch my train, which was pulling into the station. At the bottom of the stairs a woman was lying on the ground, flat on her belly, arms and legs spread akimbo. It seemed like she had just fallen. People were coming to help her, and I was about to do the same when suddenly I found myself airborne for a moment before landing smack on top of her. I must have tripped on the same step she had. She screamed, and I was so embarrassed that, despite the ripping pain in my ankle, I hobbled onto the train right before the doors closed. By the time I got to the office, my ankle was swollen and I needed crutches. I stayed home from work for a week, my leg elevated and iced.

The man in Mexico called to see how I was doing. Our conversations were so easy. Too bad he lives so far away, I thought. “Should I come visit you?” he asked. I paused; I pictured the man at my office, wondered if I were thinking about him too much. “No, let’s wait till I’m better,” I said.

Val came over and kept me good company. As we watched What’s Eating Gilbert Grape, he sat close to me on the couch and held my busted ankle in his lap. His hands were warm and he made me laugh. Damn, I thought and looked away.

After a week, my boss got me a car service to Manhattan. I was surprised at how happy I was to be back at work, in a job I didn’t care for.

Several weeks after that, my coworker dropped a note on my desk as he passed. It said that he couldn’t stop thinking about me, and when I turned to watch his retreating figure, he glanced back and peered at me longingly. “Oh God,” I thought.

A few days later, we kissed and it was exceptional. After that it was hard to take our eyes off each other. We kept it a secret, didn’t tell anyone. I saw the relationship as a dead end, yet I couldn’t stop myself from seeing him after work for dinner or drinks. I would go back to Queens feeling both exhilarated and awful. This went on for months. “I guess you are sowing your wild oats,” my mom said one night when I came home late. “Ma,” I said and went to my room. What was I doing? I was wasting time.

Val and I went to the Angelika with our friends to see Leon: The Professional. Afterwards, the man from the office came to meet me, and I introduced him to Val. As we walked away from Val on Houston Street, he said, “That man is in love with you.” Then he lit up a cigarette.

One evening Val gave me a ride home after a night out with friends downtown. “How come I’ve never met your dad?” he said.

“Because my dad is in prison,” I said.

There was a long silence as we traveled along the L.I.E. “Oh,” he said. “When will he be home?”

“Ten years,” I said, “hopefully less.”

“Why? I mean, what did he do?” he said.

“Nothing, but they accused him of being an arms dealer,” I said. “He is innocent though.”

“Yeah, of course,” he said.

My father returned after four and a half years, and that first night I felt so light, like I could float away with pure happiness.

But a few days later, the morning after a night at the theater, my mother died unexpectedly. She was my center, my sun, the reason I never wanted to leave New York City, and now she was gone. I didn’t know how I was going to live without her. I was unmoored.

Val and the man from the office came to the funeral. The man from Mexico arrived a few days later, and I realized with certainty that I wasn’t ever going to marry him.

While he was in prison, my father and I had written each other daily. He knew things about my life that my mother hadn’t, and I shared things with him that I wouldn’t have in person. I told him all about the man in the office, all about the man from Mexico, even about Val. I also told him how alone I felt.

Before my mother died, the bank had given me two tickets to Cirque de Soleil, and at some point my dad and I were on a bus together heading to the show. “Dad,” I said, “I don’t know how to do this life.” My father put his hand on my arm as I started to cry. He said nothing. He just looked down, and this made me cry harder.

Time passed slowly. Val became my constant companion and one of my closest friends. We planned a trip to Italy with the woman who had thrown the party where I’d met him. When the woman canceled, Val and I ended up going alone.

We spent ten days in Rome and Positano and Sienna. During that time, Val made it clear that he wanted to be with me, maybe forever. “Stop seeing him,” he half-whispered. At that instant, there was a shift.

Even though Val had been born in Iran, he had no accent. New York City was going to be home for him. “What will it take?” he asked me.

“I want Jewish children,” I said.

That night he took my hand as we walked, and it fit perfectly in his. We kissed, and afterwards he said, “Are you in love with me yet?”

I knew he was joking, but he looked at me so hopefully, and I felt myself stumbling, falling, in the sweetest of ways.

When I got back from Italy, I told my father that Val was the one. I also told him that the man at the office was not letting me go easily.

A few days later, my dad, Val, and I were having dinner at the round table in our kitchen when the phone rang. It was the man from the office. “I can’t talk,” I said into the phone.

He called again, within minutes. My father stared at me when I hung up the phone on the wall. “What is it?” he said.

“It’s him.”

“If he calls again, let me answer.”

We ate quietly as I willed the phone not to ring. Two minutes later it did. I sat with Val at the table while my father answered in the living room. I stood and followed him. My father sat on the couch, smiling, his head cradled in one hand, speaking in Arabic, his native tongue. I heard him say all the charming Arabic words of introduction and greeting. Then I left the room and paced in the kitchen. “Shit,” I said and wondered what Val was thinking. A few minutes later, my father came to join us at the table.

“Tomorrow, when you get to work,” he said, “ask for a transfer.”

My father had unleashed me from the green-eyed man who smelled like Galeries Lafayette.

A few months later, Val proposed, and I met his parents and his Persian friends.

At a party on Horatio Street, a few women took me aside. One of them said, “So, how do you know Vahid?”

“Who is Vahid?” I said. Then I realized that Val was the name he had adopted when he came to this country and lost his accent. I wanted to tell my ex-coworker that he had been right about the fake name, but that time had passed.

I heard that he married a woman his mother introduced him to and lives in Lebanon or Dubai or Cairo.

The one in Mexico stayed in Mexico and remains a friend.

I have been married to Val for thirty years. Sometimes I call him Vahid.

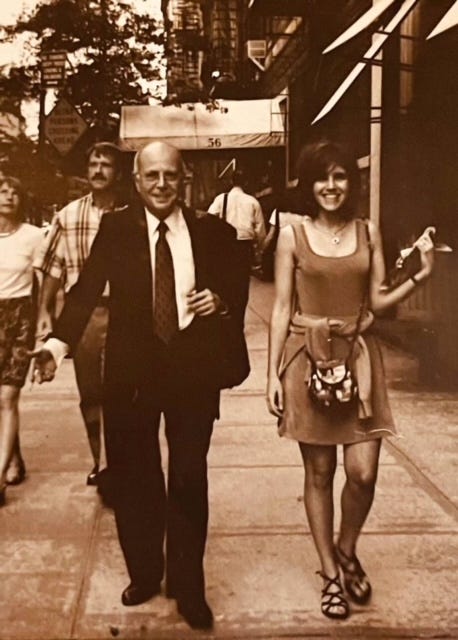

With my father on West 65th Street.

Salam Leslie Jan.

I took a short break from reviewing a boring EPA document on RCRA corrective action?

Nice break! Enjoyed it.

Love the photo - such beauty!